Cornelia Oberlander: Landscape Architect

Breathtaking. Poetic. Unforgettable. Charged with meaning.

This is how landscape architect Cornelia Hahn Oberlander and her work are often described.

Keep reading to see how learning about her approach to design can impact your own projects.

About Cornelia Oberlander

Just one month shy of 100 years old when she passed away in 2021, this German-born Canadian not only significantly impacted the design world, but she developed and improved living environments for people across all economic classes.

She was ahead of her time as an early proponent of sustainability, liveable landscapes, advocacy, rewilding, community consultation, creative play space for children, and pedestrian-friendly accessibility.

Cornelia Oberlander’s Education and Early Career

One of the first women admitted to the Harvard Graduate School of Design, Oberlander was greatly influenced by her professor Walter Gropius. Gropius, a proponent of modernist architecture, believed landscape design could improve society in meaningful ways.

Oberlander began her career in Philadelphia, then in Vermont, and finally moved to and founded a small landscape architecture firm in Vancouver, BC, Canada.

Quickly becoming known for connecting art and architecture within urban natural settings, Oberlander designed truly unique residential landscapes and playgrounds in her early career. These spaces often incorporated unexpected elements — like vegetable gardens alongside highways — in low-income areas.

Later in her career, she continued addressing challenges created by “increasingly crowded urban regions” and worked on larger, more complicated commercial projects to design solutions.

Today, her work continues to inspire landscape architects all over the world.

Most Famous Works by Cornelia Oberlander

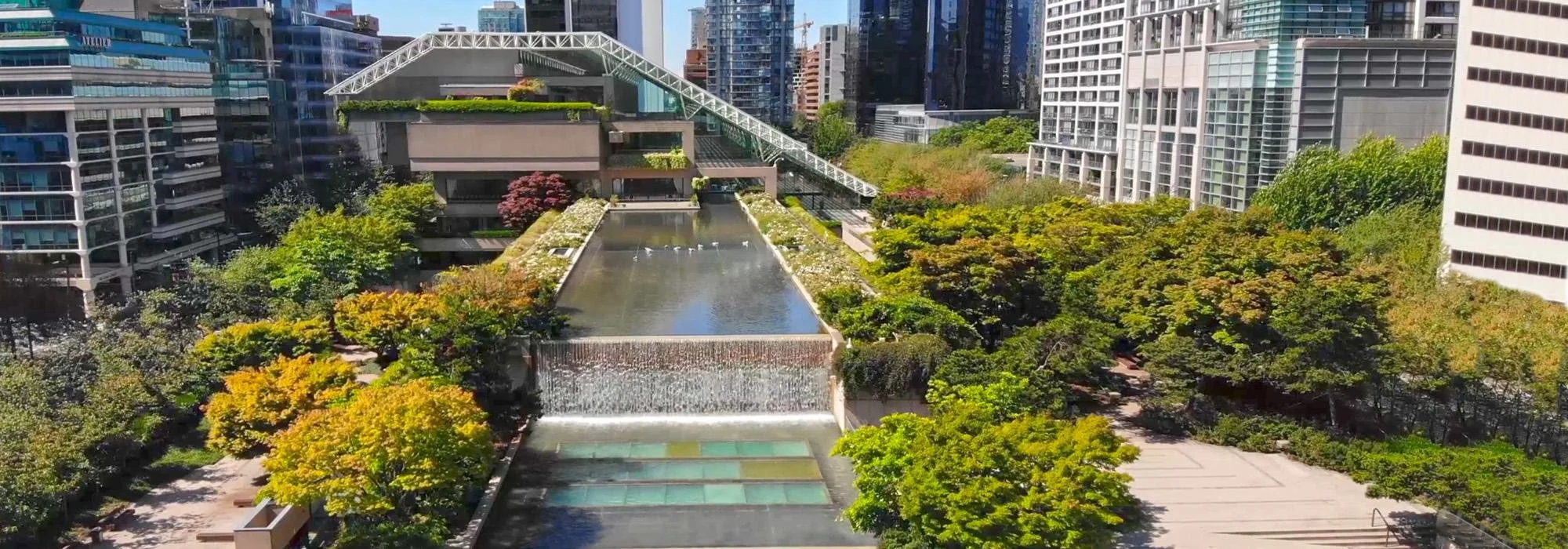

Robson Square

One of Vancouver’s most recognizable locations, Robson Square brought a natural oasis and the first green roof into the city.

This complex example of modernist architecture combines vertical and horizontal elements with terraces and pools and masterfully creates dramatic interest by offsetting concrete and glass with lush greenery.

Oberlander combined magnolia and rhododendron with Japanese maple trees and pines to achieve an unexpected degree of calm in a bustling downtown area.

Image Source: (1)

C.K. Choi Building

Oberlander worked as part of a team of design professionals that included architects as well as structural, mechanical, and electrical engineers to achieve a long list of sustainable goals that had been established for this project.

One of her main objectives was to minimize the environmental impact of construction and preserve a surrounding forest. As such, she insisted that the project be entirely located within the boundaries of a former parking lot and that none of the mature trees that covered 70 percent of the site would be removed.

Because Canadian building codes at the time were not set up for prioritizing the use of recycled materials, the team had to operate in a sensitive and strategic way to work with building authorities.

The outcome was quite revolutionary:

The building incorporates more than 50% recycled materials.

During the project, the team was able to divert close to 95% of construction waste from landfills.

By selectively pruning tree canopies, the team maximized natural light throughout the building. (This was especially effective in a place like Vancouver, where it can be very rainy and dreary, and you need all the light you can get!)

Topsoil was generated via composting toilets that unburdened local sewer systems at the same time.

The team recycled all excavation materials.

Image Source: (2)

Museum of Anthropology at UBC

Oberlander landscaped 11 acres of grounds that surround the concrete and glass structure designed by Canadian architect Arthur Erickson.

Because the museum sits upon land owned (and never ceded) by the Musqueam people, it was important to Oberlander to incorporate a permanent reflecting pond surrounded by plants traditionally used in Musqueam culture. In fact, a second phase of construction was added to the project in order to add a courtyard to house the pond. Without it, Oberlander refused to consider the project complete.

Image Source: (3)

National Gallery of Canada

Inspired by A.Y. Jackson’s Terre Sauvage painting of a rocky landscape against Black Spruce trees, Oberlander set out to incorporate plant species that would encourage up-close observation.

Relentless in achieving her goal, she finally convinced stakeholders — after five attempts — that her plant choices would thrive in the local limestone.

Image Source: (4)

Northwest Territories Legislative Building

In this project, Oberlander was determined to honor the previously undisturbed landscape of this eleven-acre lakeside site. Subarctic climate, remote location, and rough terrain were among the many challenges Oberlander faced.

To achieve her goal of blending structure and landscape, she deployed innovative strategies like propagating seeds and cuttings from the site to develop a planting plan that was entirely native to the location.

Image Source: (5)

Oberlander’s Connection to Nature and Green Spaces

Understanding that simplicity in design isn’t dull or plain, Oberlander stayed away from the trend toward busier planting in landscape design during the 1980s. She believed that even the most simplistic landscape design could be elegant and therapeutic.

By combining buildings with berms as well as rooftops with gardens, Oberlander truly believed that design could unite people and help them rise above their troubles.

In fact, Oberlander once used a $50K design prize that she had won to pay for research about the negative impact of overdevelopment, lack of affordable housing, and disappearing green spaces on physical and mental wellness.

Oberlander on a Child’s Right to Play in Urban Environments

Throughout her career, Oberlander sought to enlighten city planners and developers about the critical role playgrounds could play in child development. Then she encouraged them to incorporate playgrounds in urban construction.

As she developed practical proposals for the specific playgrounds, Oberlander specified inexpensive and recycled materials — like sand, water, logs, and tires — in her design plans and identified vacant lots where playgrounds could be constructed.

To properly maximize the benefits of the playgrounds and the free play that would take place there, she believed that designers should seek input from the children themselves.

Key Takeaways from Cornelia Hahn Oberlander’s Work

Cornelia Oberlander was a trailblazer who never fully retired. She believed that everyone deserves the right to enjoy green spaces that have the ability to nurture emotional well-being.

Key takeaways and design principles from her work that continue to inspire landscape designers and architects today include:

Rooftop gardens that trap and recycle rainwater and cool underlying buildings

Turning to native flora in order to deliver a sense of peace to users of a particular landscape

Using landscape design to address social and environmental obstacles

Learn More

Feeling as inspired as we are by Cornelia Hahn Oberlander? Put that inspiration into practice today with PureModern planters.

References:

(1) www.tclf.org/robson-square

(2) www.tclf.org/ck-choi-building

(3) www.tclf.org/museum-anthropology-university-british-columbia

(4) www.gallery.ca/magazine/in-the-spotlight/landscape-art-and-architecture-cornelia-hahn-oberlander-at-the-national

(5) www.tclf.org/northwest-territories-legislative-assembly-building